During the early days when I first started producing shows; learning the basics of marketing, branding, sales, and strategy were often forged through trial and error. Without a formal education to rely upon, I followed what other groups were doing, and I taught myself by reading books and online sources. I noticed an interesting pattern emerge from the reading material; each source was essentially saying the same things. The real value came from the way they approached a problem to find a solution.

This is why I’ve chosen to describe an early experience starting out. As a beginner, I didn’t have a by-the-book answer to figure what I was doing. But I didn’t go into it blind either. If you’re considering stepping up to produce your own shows, it’s worth investing some time to figure out how to sell a show. I admit that I wasn’t great at marketing but I took steps to understand what I needed to do to find an audience for my offerings.

I hope this post will be helpful by showing you how I applied my very rudimentary knowledge of marketing to produce an event. By studying my early actions, a promoter, artist or even a new venue operator might gain some insight from my approach to concert marketing and promotion. This is not a “how-to manual” with bullet points, it’s a study of someone starting out who really had to learn as they go. Though the event I describe took place over 20 years ago, those early days would define my later career.

The Setup

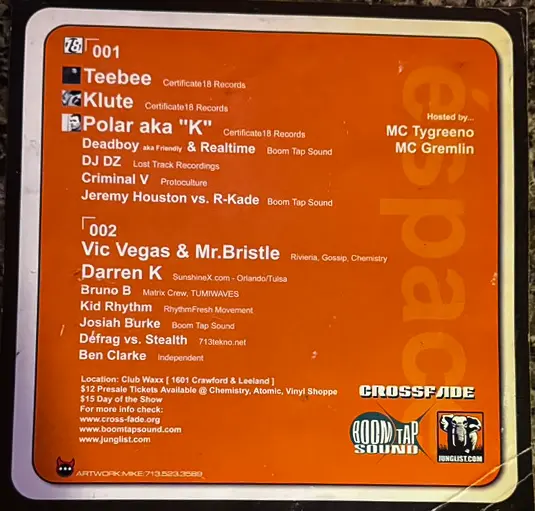

The story I want to tell involves producing a drum n’ bass event at a venue known as Club Waxx in Houston, Texas in 2001. The event was called ÉSpace with headlining artists from the Certificate 18 label: TeeBee, Klute and Polar.

The naming of the event came from a French word to describe a cultural space or a sense of balance with negative space (the person who coined the name for the show had French origins). Despite the obvious connotation to the negative aspects of rave culture, we thought it was a non-issue and went ahead. In fact, we could’ve produced the event without it naming the event but, it was something that most rave promoters did at the time and we were playing it safe.

Back then, the company name we produced shows under was called Crossfade Productions. The ‘crossfader’ is a switch that sits on a mixer and allows a DJ to fade in from a left channel and a right channel to blend the sounds of two separate music tracks. If you judged us by our name, you could probably guess that we were involved with DJs or the nightlife. And that’s part of the brand, creating a name that feels relevant to the type of shows we wanted to produce. We started the company as something fun to do but we treated our operations with all the seriousness of running a legal, tax-paying business.

A Wild Opportunity Appears

It helps to understand how we came about working on ÉSpace. I had friend / co-partner get approached about partnering in the show with another promoter. This promoter was actually a collective of DJs who worked at a vinyl record store. Their collective produced primarily drum n’ bass shows so that’s how we came about working with that genre.

Although I didn’t really let it be known, I wasn’t a huge fan of drum n’ bass, or jungle, it’s more aggressive sounding relative. There’s something to be said about working with what you knew. Though I wasn’t huge into that style of music, the community of friends and colleagues I often found myself fraternizing with, were themselves huge into the drum n’ bass scene.

We weren’t novices to the market we were trying to sell to. We understood the movement, the major artists, and the motivation of a typical fan that attended those events. That wasn’t the only rationale that made business sense to do the show. The biggest reason had to do with brand power; they had it, we didn’t. They also had a proven history of producing drum n’ bass shows. They had deep ties with local scene, they could rally their supporters to spread the word, leverage relationships to reduce vendor costs, and supply the backline production.

Crossfade had hoped that by going into a co-pro agreement, it would increase our brand value and market presence. We viewed this as a strategic partnership that would bring us several benefits. If we showed that we were involved with producing shows with touring talent, it would elevate our rank within an unofficial promoter hierarchy. I can tell you now that this line of thinking is completely scatter-brained.

There have been many promoters that have come before and after, who produced events, and didn’t need to rely on a “shiny object” to deliver quality entertainment. They just needed to be consistent and trustworthy. For our contribution to the partnership, we would add marketing support and most importantly, a sizable chunk of the capital needed to produce the event.

Booking The Talent

As previously mentioned, our partners had key relationships, which also extended to talent agencies. The agency I ended up doing the booking through was called Flammable Productions based out of San Jose, CA with an agent called Leo Corston. The date we decided on was Saturday, April 14. The tour name, Certificate 18, came from the record label where all the artists had released tracks with.

All the artists we booked were based overseas. Both TeeBee and Polar/K hailed from Norway while Klute came from the United Kingdom. We used this factoid as a marketing byline because we weren’t just booking stateside talent. There was a perceived value that foreign artists within the dnb industry were just better. There were other areas we were able to exploit for the purposes of marketing.

Two unique marketing angles manifested themselves which occurred by chance. The first opportunity came about when we were told that this would been the first U.S. appearance for TeeBee and Polar. These small selling points can have impact and increase the prestige of the event. It’s not often that an audience gets to make a first impression on an artist, rather than the other way around. The second angle, I will present a bit later in this piece but it also came with a downside.

Aside from the talent fees, we had to cover flights and hotel. Today, this is something that is exceptionally rare for promoters to do unless it’s a one-off event because it can be unpredictable.

Foreign artists try to lock in multiple bookings before their trip because traveling overseas and managing the logistics for a one-off booking can increase risks for a promoter. This show was not immune to such an outcome. Unfortunately, one of the artists, Polar/K ended up not being able to perform. He may have been unable to secure the correct work permits, or there may not have been available flights. Whatever the reason, it was a regret that he couldn’t be a part of the fully advertised line-up.

The Space Must Make Sense

Club Waxx, also known as the ‘Waxx Museum,’ was a former gas station with a service center. There were still roll doors for the entrance and the main events would take place where cars used to get their tune-ups and oil changes . The retail section functioned as side room or a spill-over room for attendees who wanted to take a break away from the main event.

If a touring act was playing the main room, the side space would turn into a spot where that band or artist could sell their merch. The front of the venue was cordoned off by a chain link fence. This fence had the benefit of expanding the venue’s capacity and acting as a patio for congregation. You could also find vendors selling homemade trinkets, CD’s, and a plethora of other colorful menagerie.

If you were a fan of underground hip-hop, there were only a few venues you could visit that would feature up and coming artists as well as local favorites. At the top of that list stood Club Waxx. This venue made the perfect sense for the type of show we wanted to do.

Drum n’ Bass had some crossover with hip-hop and its audiences. The graffiti covered walls on the exterior along with its gritty atmospheric interiors lent itself well to crafting an image you would associate with counterculture music. To an outsider, seeing a chain link fence would send off warning signs. For the people that attended shows there, a chain link fence enhanced its “realness” and authenticity.

Lets Go, We Now Have A Show!

Once the contracts were signed and the deposits sent, we now had a show we could promote. This moment felt like validation. Here, we were going to etch our own mark in music history. Fast forward to today, only a select few would remember what we did then. While we were negotiating contracts and organizing flights, our partners set about designing the creatives, working with the venue, and teasing the date. We were only a few weeks out from the show which I felt was rushed.

An optimal time to market a small club show should rest between 6 to 8 weeks minimum but no more than 3 months. The longer the lead time, the more time to promote. Having too much lead time might cause your marketing to be ignored due to visual fatigue.

There was also a greater chance that another promoter could drop a competing event on your date. Within your promotions window you should have the time to build hype, pass out flyers, and recruit more promotional support.

Probably one of the most effective tactics involving passing out flyers at upcoming shows where you knew that audience would be interested in attending your event.

So the longer the promotion time, the more opportunities to promote at other events might exist within that timeframe. This was a time tested marketing formula to ensure a greater chance of success.

How do you measure success? For us it was easy, we just wanted to at least break-even. If we made money, then that’s a bonus but getting back what we put in was the goal. And I think starting out, that should be the aim of every new promoter. Don’t be swayed by stories of promoters walking out of venues with a backpack full of cash. To be sure that happened, but that’s not a common experienced shared by most. By recouping what we spent, we could turn around and produce a follow-up event in order to keep the cycle going. Then bigger things would follow or so we naively thought.

Having A Brand and Marketing Strategy

A crucial part of marketing is having a brand strategy. When Crossfade Productions first started, none of us had any knowledge about branding or the business of marketing. But the steps we were taking to publicize our name was in part, creating a brand identity. We knew that we wanted to gain a following, develop rules on how we operated, book a certain genre of music, and increase our profile.

There was a period of self-learning where I taught myself HTML so we could setup a website, mostly to sell tickets from. I made business cards, email addresses, designed a logo, and conducted extensive research to find the right communication channels to get our message out to the public.

These actions are all part of the branding process but it ultimately leads back to two fundamental questions. How do you want your audience to view you and what type of reputation do you want to be known by?

I was following a basic script but I acted without purpose by copying what others had done before. In a way I stumbled into an important aspect of marketing through the use of imitation and common sense intuition.

The next few weeks before the event took place became a whirlwind of activity. Going out almost every night to selectively target venues and parking lots with flyers. Distributing flyers to retail locations that experience significant foot-traffic. Going online and promoting on message boards, chat rooms, and public event calendars. And using every free resource available to maximize the reach of viewership. This leads back to marketing frequency which helps enable messaging recall.

Frequency is the key to memory. Frequency is the key to learning and retention.

Word of mouth marketing is very powerful because if you can get people talking about your event in a positive way, it may convince others to attend. Of course, we know it as creating “buzz,” and it’s not new or groundbreaking. By summing up all our concerted marketing activities, the goal push forth an image of something not to be missed. In time, consistent messaging would enable a tipping point where organic virality would then take over.

Saying Hello and Bidding Goodbye

I did mention earlier that there were two unique marketing angles that we were able to capitalize on. The first angle, we would promote the debut the first US appearance of a foreign artist at our show. The second proved to be more bittersweet. The Houston Sports Authority had extended an offer to the owners of Club Waxx to buy out their property, which they accepted.

The building was going to be torn down, and a parking lot for a new basketball arena would spring up in it’s place. We were given notice that our show was to be the last show that they planned to host there before closing the doors for good. We had high hopes that we would continue a string of events but instead, our first show at Club Waxx would become the last show at Club Waxx.

The next step was obvious. Don’t let a good marketing opportunity go to waste. And for the short remaining time we had to promote, we pushed messaging that our show would be the last show held at Club Waxx.

In hindsight, we should’ve added a hip-hop act into the side room as a tribute to the music that it was known for. If there’s a chance to drive increased attendance by creating a hybrid lineup that works, then go for it. It would have also opened us up to a fresh audience. And, it would’ve helped alleviate the anger from promoters who had much deeper ties to that venue who felt they deserved to be the ones to produce it’s going away party.

As fate would have it, it just happened to be our show that became the last. We weren’t the ones who made that call yet we received some criticism for being put in that position. You have to work with the hand you’re dealt.

It’s Showtime

On the day of the show, we ran the box office staffing, wrote online posts, sent out texts, and made calls to friends and supporters reminding them of the show.Then we just waited for doors to open and the crowd to show up. All the artists had arrived without incident and checked into their hotel.

Our partners handled the artist hospitality, got the backline setup, tested the gear and verified there were no technical issues during soundcheck. They even added two decorative flame lamps to either side of the turntables.

These lamps had motors in their base that pushed air upward causing pieces of fabric to flap. A modulating red to orange light emitted from it’s base upwards which enabled it to create the illusion of an actual flame.

The first time I saw the lamps was during the performance and I had a hard time discerning whether it was real or not. They were such a small visual element to the production but it boosted the crowd excitement of an event that was already full energy. Those two flame lamps became one of the most memorable things I recollect from the show.

When the doors opened, a steady crowd started to stream in and eventually fill up both the main room and the side room. Although there was a healthy attendance, it wasn’t completely shoulder to shoulder which allowed ample room for people to dance and move. But, as a promoter, you want a room to feel more “cosy” because then you knew that you had a better chance of being “in the green.”

This may already be a cliche, but organizing an event, bringing together a group of people who shared a common bond through music, and seeing it in action is an inspiring thing to witness. That feeling can become addicting because once the moment is over, you’re ready to do it again. As the show got going, everything ran on automatic pilot for the rest of the night until the end. When it ended, I got a chance to speak to some of those who were in attendance. Their responses ranged from enjoyment to high praise. It was affirmation that we put on a good show. It was a fitting send off for a very cherished venue.

Was It Worth It?

A few days later when we had time to accrue all our expenses and balance it against our revenues, we realized we didn’t make money. That was actually a pretty common outcome for us at the time. While it was a fun activity, we were disappointed because we couldn’t make it work even with all the extras we had going for us.

Taking losses is never fun. Did we learn lessons from the experience? Absolutely, but we weren’t in school. This was a group effort that fell short. I can’t conclusively point a finger at any one thing that we did wrong other than having the extra lead time to promote might have pushed us over the top, or even adding a local hip-hop support act would’ve drawn a different audience segment to the show.

There are only “what-if” scenarios left to figure out. Maybe this works. Maybe it does not. That is what you review in a postmortem.

An argument can be made, rather logically, whether our brand was mature enough to produce this show? Either you throw shows to grow your brand and experience hardship along the way or forget about doing shows altogether. Everyone starts somewhere, and our start was here.

Where Does The Story Go On From Here?

So that about sums up one of my early experiences producing an event with a headliner. I’d like to say we went on to do many more successful shows in the future, but the reality is, we lost more than we gained. Not too long after, we decided to call it a quits and move on.

What I didn’t know then is that the early experiences proved to be an instrumental part of my growth. A door opened that lead to a career in the professional concert industry. Because of my past experience, I was able to keep it open. You never know when those moments will line up. When they do, do not be shy about going after them. They may lead you to the future you’ve always wanted.